AC Space

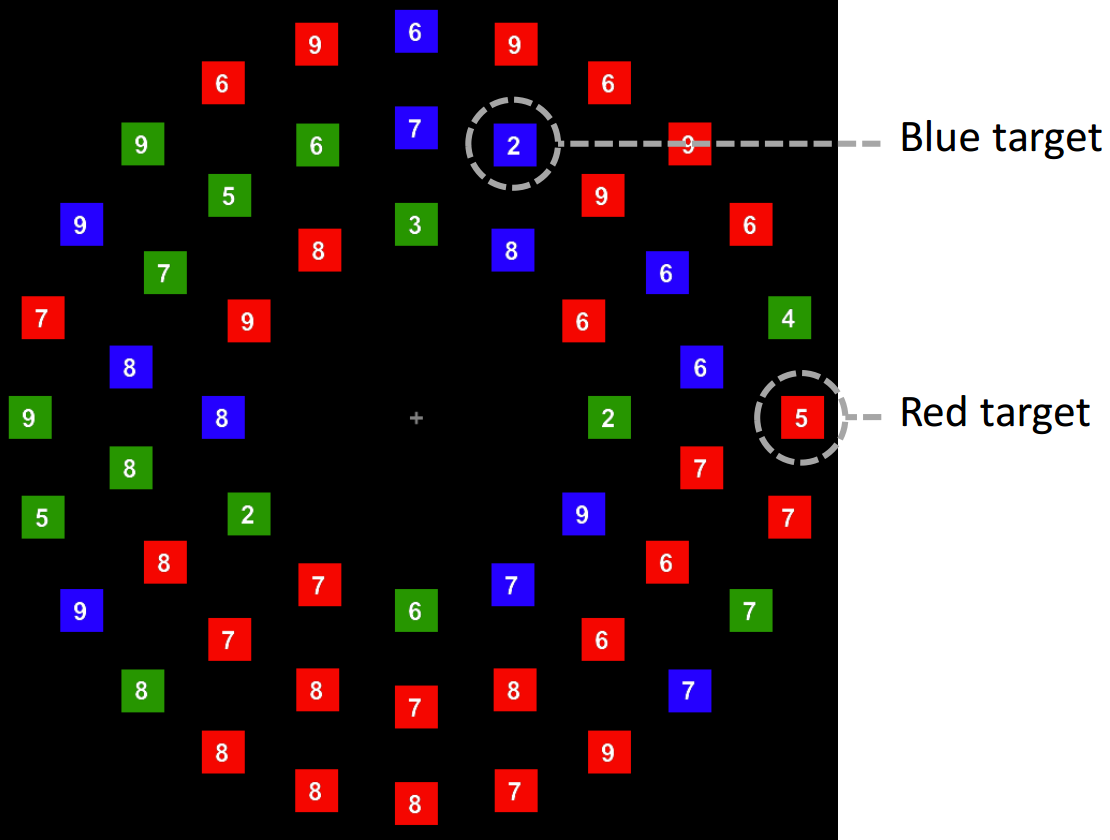

According to anecdotal evidence from my lab mates, the ACVS is one of the more popular experiments among our mTurkers. Indeed, look how colorful the display is.

This project is based on the findings of the Adaptive Choice Visual Search (ACVS) task developed by my adviser Dr. Andy Leber

A Quick Read

When searching our visual environment, we often have multiple strategies available (e.g., when looking for your favorite apples on a supermarket shelf, you can either look for the red ones or the round ones, or just serially search through all items). How do we choose a strategy? Recent research on this question has revealed substantial variation across individuals in attentional control strategies. Moreover, while attentional strategies have been found to be reliable within subjects, they have failed to generalize across different paradigms that assess various components of strategy use (Clarke et al., 2018). Thus, evidence for whether strategies generalize beyond a single paradigm remains scarce. While previous tests of generalizability used paradigms that vary in many ways, here, we foused on a single strategy component that could be preserved across tasks, while making several other changes. In two experiments, we assessed the correlation between individuals’ strategies in the standard adaptive choice visual search (ACVS; Irons & Leber, 2018) and a modified novel visual search task, Spatial ACVS. In the Standard ACVS, participants seeking to perform optimally have to enumerate subsets of different colored squares and identify the smaller subset to choose a target from. Similarly, in the Spatial ACVS, participants seeking optimal performance have to enumerate spatially separate subsets of squares (one on the left and one on the right side of the display), choosing the target in the smaller subset. Participants finished both tasks in the same order in one experimental session. Results showed a positive correlation in optimal target choices between the two tasks, indicating similar strategy usage. Future studies can focus on what strategy components tend more to be generalized across tasks and whether an individual’s strategy can generalize to tasks with a combination of several strategy components.

Introduction

Imagine you are in a stadium watching an exciting women’s soccer championship final with your friends. You are so concentrated on your favorite player and fail to notice a rogue fan rushing into the field before causing an uproar. The reason why you are unaware is that you are not paying attention to what happens outside that small area in which you are tracking the player. Since we are not able to fully process everything in our visual field, a selection process must happen, leaving only a fraction of the visual activities for our conscious mind. Such selection processes happen in every second, one of which is enabled by visual search.

- What makes someone faster than others in finding some object? Of course, some people are born with more ability, but the strategy used in visual search also accounts for a large proportion of how efficient the search is.

Let’s stick with the soccer player for another moment; what does she do when she wants to pass the ball forward to the striker? While the striker is surrounded by many defenders, she knows that she can either look for red shirts or blue shorts because that’s what her team wears. But imagine when the opposing team wears shorts that closely resemble blue—maybe indigo. In this case, trying to search for blue shorts gives the player less of an advantage, since she needs to search through more potential targets to locate the striker. In this example, the strategy that the player uses is not a good one that will yield efficient search. While it seems intuitive that people always try to use a good strategy to benefit their performance, recent research found that people’s visual search strategy is far less than optimal (Irons & Leber, 2016). Visual search is not limited to sports—many responsibilities, including airport baggage screening and radiological image reading, involve visual search.

- Why do people consistently use sub-optimal strategy? Can we improve people’s strategy by training? To answer these questions, there is a need to understand visual search strategy in a more comprehensive way.

The importance of strategy in visual search, however, is contrasted with a rather limited body of research on visual search strategy (e.g., Kristjánsson, Jóhannesson, & Thornton, 2014; Irons & Leber, 2016, 2018; Nowakowska et al., 2017). One of the recent studies that have made a successful attempt on characterizing individual differences in visual search strategy introduces a new visual search paradigm—the adaptive choice visual search task (ACVS; Irons & Leber, 2016, 2019). Different from traditional visual search tasks where participants are typically asked to search for only one target in each trial, the ACVS paradigm involves a display where two targets are present. However, only one target is considered the “optimal” one (see figure 1). Researchers are able to assess an individual’s strategy use with two key measurements in the task: the proportion of optimal choices, which is the percentage of trials in which participants choose the optimal target, and the switch rate, the percentage of trials in which participants switch between two target types. Efficient searchers who complete the search task faster than others typically select more optimal targets and avoid unnecessary switching during the experiment, showing a high proportion of optimal choices and lower switch rates. These two crucial parameters, then, grant the ACVS the ability to improve the current research of goaldirected attentional control by adding strategy measurements to the methodology toolbox beyond traditionally used reaction times and accuracy. Studies with the adaptive choice visual search task have shown a large range of individual differences in the proportion of optimal choices and switch rates (Irons & Leber, 2016), both of which have also been proved to have good test-retest reliability, suggesting a trait-like behavior pattern (Irons & Leber, 2018).

Questions

Suggested readings